Desert Camping Tips at Organ Pipe National Monument

In 2022, only 133,317 people visited Organ Pipe National Monument. One reason why it probably doesn’t get much traffic is that the park is in the middle of nowhere. The closest “real” grocery store is about 40 minutes away in Ajo, and the monument borders Mexico. Yet, if you are looking for a true camping experience in the desert surrounded by mountains and home to cholla, prickly pears, saguaros, and park’s namesake cactus, there’s no better place. In fact, Organ Pipe National Monument is the only place in the United States where you can see the Organ Pipe cactus growing in its natural habitat.

About the Organ Pipe Cactus

What is the Difference between an Organ Pipe and Saguaro Cactus?

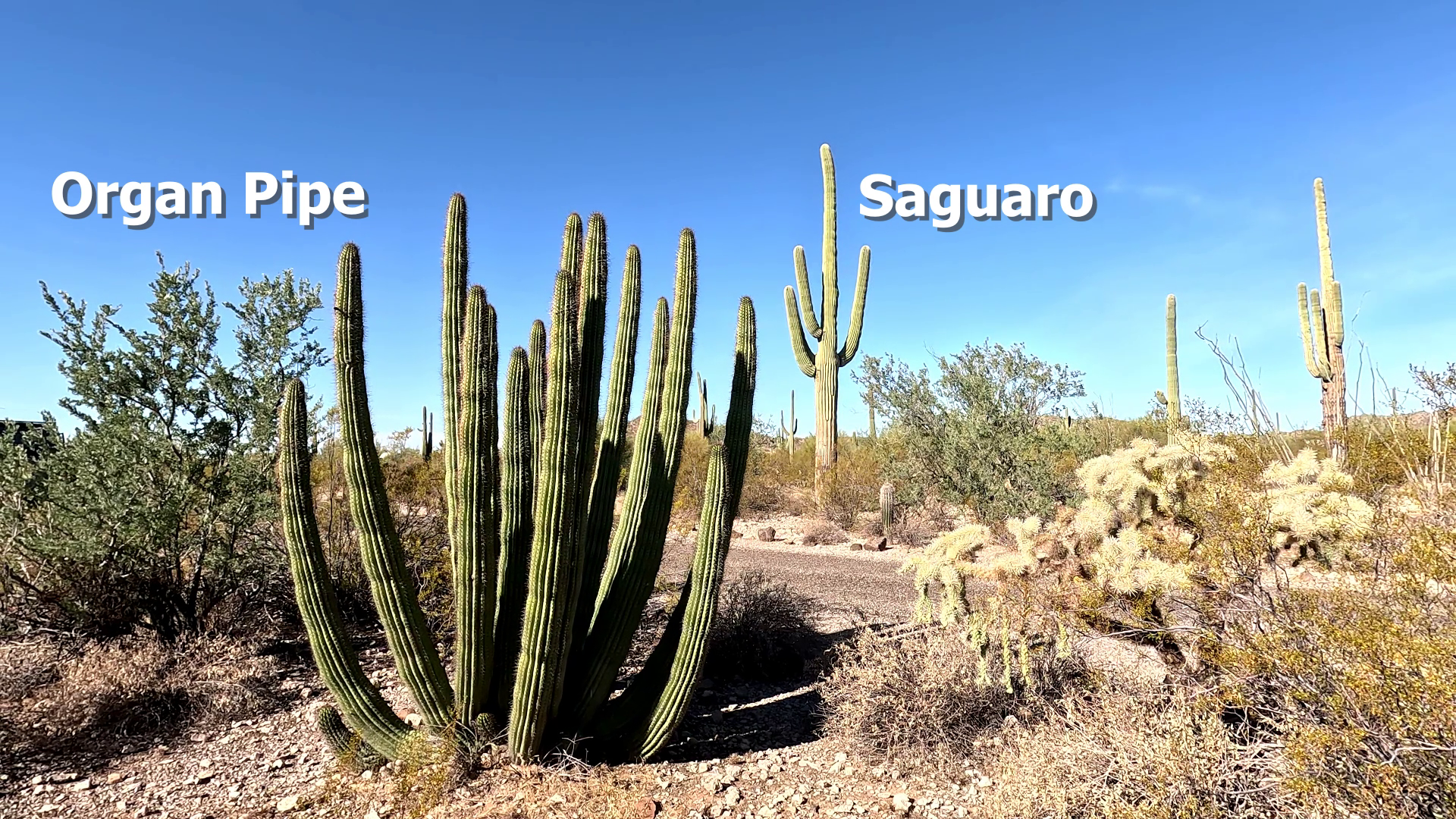

It's easy to tell the difference between a Saguaro cactus and the Organ Pipe cactus.

The Organ Pipe cactus starts its life as a single “trunk” from which additional stems branch out near the ground. In contrast, the Saguaro branches anywhere along its trunk.

Pro Tip: A large population of the Senita cactus (a/k/a Old Man Cactus because of the “beard” at the tips) can be found in Senita Basin within Organ Pipe National Monument.

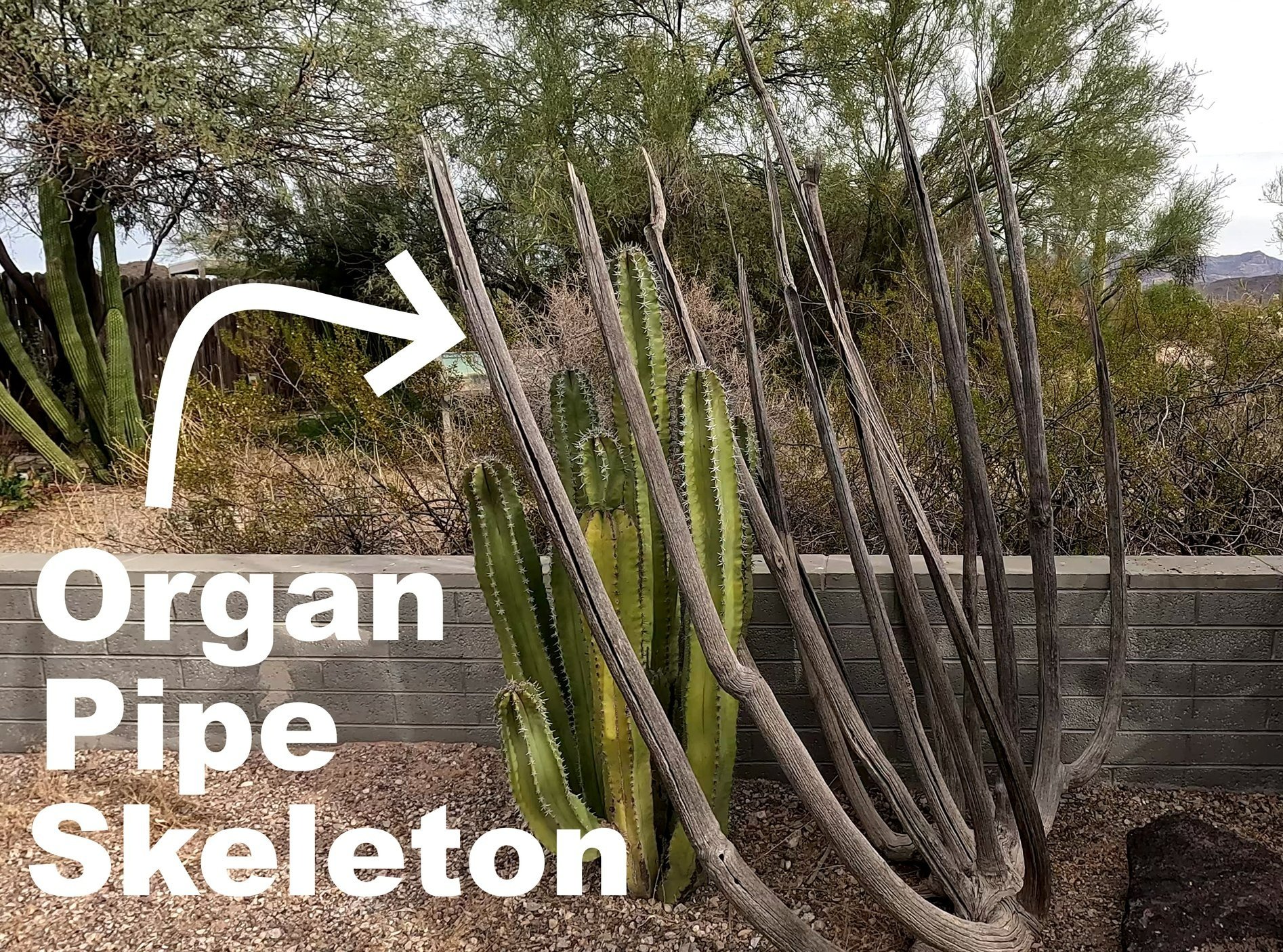

How did the Organ Pipe Cactus get its name?

The scientific name for the Organ Pipe Cactus is Stenocereus thurberi. “Stenos" means "narrow" and "cereus" means "candle." Personally, I think that the Organ Pipe cactus looks more like a candelabra than a set of organ pipes. Yet, the cactus got is common name when European settlers looked at exposed skeleton and were reminded of the pipe organs in the cathedrals back home. As for “therberi,” that part of the name comes from George Thurber, an 19th century American botanist who studied the cactus.

How does the Organ Pipe Cactus Bear Fruit?

During one of the evening Ranger Talks near the outdoor seating area near the Twin Peaks campground, we learned all about the importance of bats to the Organ Pipe cactus life cycle. Interestingly, the creamy white flowers of the Organ Pipe cactus only bloom at night (usually in May-June), and a colony of lesser long-nosed bats are the main pollinators of the flowers. The spiny fruit ripen just before the summer monsoon period. The bats eat the fruit and also help disperse the seeds throughout the area.

The Organ Pipe cactus is lucky if it can survive the first few years of its existence. For the first 10 years, the cactus may be no bigger than a few inches and is prone to being trampled by animals or being washed out by heavy monsoon storms. It’s not until age 30 that the organ pipe cactus will grow its first stem. Each stem grows from the tip, rarely branching, and grows approximately 2.5 inches per year. Remarkably, the cactus can live for over 150 years. Although the typical cactus may be 16ft tall and 12ft wide, we definitely saw older specimens that were much taller and wider.

Where is the Best Place to See the Organ Pipe Cactus?

While Organ Pipe National Monument boasts a couple of scenic drives and several hiking trails, I think that the best place to see the Organ Pipe Cactus is at the Twin Peaks campground located just a mile or so from the Kris Eggle Visitor Center. Organ Pipe cacti adorn many of the campsites themselves.

Several trails start near the campground – including those that lead to the Victoria Mine (2.1 miles), Lost Cabin Mine (3.9 miles), Senita Basin (3.2 miles), Red Tank Tinaja (5.5 miles), and Backer Mine (7.2 miles). A partially paved permiter trail also snakes around the campground. However, for visitors short on time, the 1.5-mile Desert View loop (which starts over by the group campsites) is probably the best to see several organ pipes and learn about the ecosystem. In addition to having several interpretive signs, the trail offers amazing views of the campground and even Mexico!

What is the Most Unique Thing about Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument?

Aside from the Organ Pipes themselves, my favorite section of the park was the Quitobaquito (rhymes with Frito Burrito), an oasis that is home to a natural spring that has been a water source for wildlife and indigenous peoples for thousands of years. The Tohono O'odham, a Native American tribe, have a long-standing connection to the area, using it for sustenance and cultural activities. The endangered Quitobaquito desert pupfish, Quitobaquito spring snail, and the Sonoyta mud turtle aren’t naturally found anywhere else in the United States.

To get to Quitobaquito, visitors must drive along the US-Mexico border for several miles on South Puerto Blanco Drive. Much of the monument was closed between 2003-2014 because of the operations of violent drug-smuggling cartels. Park anger Kris Eggle was shot and killed in pursuit of drug smugglers in 2002, and the Visitor Center was named in his honor the following year. The park reopened with enhanced security, increase border patrol agents, and vehicle barriers.

Today, there are several signs telling visitors to watch out for illegal immigration and drug activity. And of course, The Wall now separates Organ Pipe National Monument from Mexico. We never felt unsafe during our time in the park. If anything, I developed greater compassion when we would encounter the rare shirt, shoe, suitcase, or other item that once belonged to someone seeking a better life here. While people can debate the pros/cons of The Wall, seeing it in person for the first time up close was something that I will never forget.

What are Some Tips for Camping in the Desert?

There are some no-brainer tips for camping in the desert — bring plenty of water, fuel, sunscreen, food etc. I’m not going to reiterate the obvious tips that you’ll read about in every other blog. Instead, I’m going to focus on the things that we learned while camping at Organ Pipe National Monument.

Tip #1: Open Your Hood if You Know What is Good.

Everyone – I mean everyone – raised the hood of their RV and tow vehicle at night. That’s because Organ Pipe National Monument is filled with desert packrats. These packrats build houses, called middens, which are large collections of sticks, cactus parts, pebbles, bones, and garbage filled with softer nesting material – and all held together with the packrat’s highly concentrated urine. Unfortunately, these packrats love to come out at night and next in the dark cave-like space of a vehicle’s engine compartment. Moreover, those little stinkers like to chew on wires and cause all sorts of damage.

A park ranger told us that they’ve never had packrat problem with any vehicle that had its hood raised for the night. Moreover, he suggested that the packrats are less likely to feel comfortable if there the space is lighted. We placed a couple of rechargable puck lights in the engine compartment of our RV and tow vehicle and opened the hood each night. (The puck lights can flash and change color too — which is supposed to be an added deterrent).

We had no problems. Whew.

Tip #2: A Black Light May Save You.

My next tip is to bring a black light to Organ Pipe National Park. All sorts of creepy crawly things come out at night in the desert. A park ranger told us that scorpions love to crawl under rocks and attach themselves underneath things like camping chairs and the amphitheater benches. Because a scorpion glows under ultraviolet light, we got in the habit of using a blacklight to check areas if we were going to be out at night.

Kasie photographed this scorpion near one of the water spigots by our campsite. A park ranger told us that the scorpion in the photo is the Arizona Bark Scorpion is the most venomous in North America and one of the fastest in the world (up to 1 meter/second). Yikes!

Tip #3: Beware of Dogs (and Cactus).

Pets are only allowed on three trails in at Organ Pipe National Monument.

The Palo Verde Trail – 1.3 miles one way

The Campground Perimeter Trail – 1 mile one way

The Visitor Center Nature Trail – 1/10 mile one way

My tip is: AVOID WALKING YOUR DOGS ON ANY OF THE TRAILS.

Many species cactus have microscopic, overlapping scales that function as barbs. In particular, the Cholla and prickly pear cacti have evolved so even a light brush against the plant may cause a little segment of the plant to break off – which can attach to you or your dog’s coat. This is one way that the cactus spreads itself to new areas.

Our dogs (and in particular our shih tzu, Billie) seemed to be cactus magnets when we took them on the trails. Every time we would try to walk the dogs on the Twin Peaks perimeter trail, Mr. Earl or Miss Billie ended up with part of a cactus in their fur and skin. Very painful. Very hard to remove.

We quickly learned that it was better to just walk the dogs on the paved part of the trail and/or the asphalt roads between campsites. (The asphalt might not be much of an option with hotter temperatures though).